From Yell, Shetland to the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary: The Story of William Spence (1841-1881)

- Karen Inkster Vance

- Jan 13

- 13 min read

Tracing a Shetland fisherman’s journey of courage, surgery, and recovery through 19th century letters and hospital records.

[Note: This article first appeared in Coontin Kin, Yule 2025, the journal of the Shetland Family History Society. The Society supports the study and preservation of Shetland family history, and new members are always welcome.]

Some stories tug at me, begging to be pieced together and told. Such is the case with William Hoseason Spence, a humble fisherman from the island of Yell, in the Shetland Islands. Though he is not an ancestor of mine, his courage, strength, and willpower call to me. I picture his quiet dedication to his parents, wife, and children as if his life were unfolding before me now, rather than 150 years in the past.

Earlier this year, I began paging through digitized copies of the Edinburgh Medical Journal from the 1870s, hoping to discover more about him.

I am working on a project about Shetland’s Gale of 1881, known locally as the Gloup Disaster, of which my second-great-grandfather, Samuel Inkster, was a survivor. My aim is to tell not only the tale of each boat and the men who were lost, but also the fates of the widows, children, and other dependents who were so swiftly thrown into mourning and destitution. Such suffering was often borne in silence, the stories never told.

On July 20, 1881, the islands’ haaf fishermen had laid their lines when a sudden storm blew in from the north-north-west. Crews sailed toward shore amidst thick darkness, fierce winds, and roiling waves. Fifty-eight men did not make it home that night, including William Spence, whose boat Undaunted was lost on the Fustra baa, off Westing, Unst.

I gather bits and pieces like a detective: contemporary newspaper articles, oral history interviews, photos, Facebook posts, and books. I have connected with descendants of these families who share the personal, poignant details often left out of publications. From these stories arise many questions, which I try to answer through archival research.

Letters from the past

I first ‘met’ William amongst the pages of Catherine Williamson’s book, Jemima’s Journey, an account of her great-grandparents, William Spence and Jemima Mann.[1] Letters passed down in the family made the couple come alive, their struggles and devotion tangible even during courtship:

Dec 1873 Westsandwick

Dear William I received your kind letter I was much plesed when I read its contents for I realey thought that you ware onley in jest when you ware here I am sertenly very much plesed and hardley know what to think about it as marage is not for a month or a year but for a lifetime and we should pray to god to direct ous in such a proseeding for if he does not derect ous it will not be for the good of our souls therefore we ought to seek his guidens in all such importent things I am but a poor servent girl and have no other chance but to serve as long as I am unmarried…[2]

One of Jemima’s brothers had preferred another suitor, perhaps because William – though hardworking and dutiful – struggled with a painful limp.[3] Nonetheless, Jemima married 32-year-old William the following month, in January 1874, and they settled at Dalsetter, Yell with his destitute elderly parents and younger sister, whom he supported. A son, Charles, was born a year later.

Meeting the professor

Two years after their marriage, according to family lore, William suffered an accident while at the Greenland whaling. The pain in his knee became so severe that he made the difficult decision to travel to Edinburgh for evaluation and treatment. The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, a voluntary hospital financed through philanthropic donations and public fundraising, was founded in 1729. It is the oldest of its kind in Scotland, and at the time of William’s surgery, the largest in the United Kingdom.

Such a facility provided the poor with advanced healthcare that they could not have accessed locally. Regular collections were taken up throughout Shetland to support the Royal Infirmary, and dozens of Shetlanders were sent south each year for surgeries and treatment, staying an average of thirty days in state-of-the-art facilities.[4] Advertisements in the Shetland Times also sought young women “of good moral Character” to work as Ward Assistants, to do heavy cleaning and assist the nurses.[5]

While Edinburgh’s surgeons were at the forefront of scientific study, success was far from certain. As William started out on the painful journey south, he wrote home:

Bressay post office, Thursday Aug 1876

Dear and much loved Jemima

… keep up with a good hart I trust in Gods mercies that we will see etch other a gain you must alwise write to me So with kindest love to you and our Dear Child and to Father Mother and Sisters

I ever Remain, Dear Jemima your Ever Affect Husband

Wiliam Spence[6]

William was placed in the 18th surgical ward under the oversight of Professor James Spence (no relation), referred to by William as“the professer”: “…he wants me to have rest for awhile so that he may see how my leg gits on and to know what the diseas is exactly so that he may know how to treat it.”[7]

Professor Spence was tall, slightly stooped, and often wore an “anxious, half-sad” facial expression, so much so that colleagues called him ‘dismal Jimmy.’[8] Though conservative in his views—he wasn’t completely convinced of the germ theories promoted by his younger colleague, Joseph Lister—he was a capable and skilled surgeon with a high recovery rate. By 1876, he had been at the Royal Infirmary for over three decades, with his early years spent as anatomy demonstrator and lecturer.[9] One contemporary wrote: “He had so intimate a knowledge of anatomy that every step in a difficult operation was foreseen.”[10] William was in good hands.

It must have been difficult to lie on his back all day, his splinted leg raised in a cage, and his knee covered with steam plasters, but he never complained: “I am well attended and has plenty to eat and if I could use more it would be given.”[11] Edinburgh was full of Shetlanders, and William received frequent visitors who brought tobacco, writing paper, a few shillings, or anything else he needed. Even the hospital workers became friends: “…the young doctors when they have time comes and sits down at my bedside and tells me all what great operations they have seen porformed and the way that is was done so they will have me taught to be a doctor yet and they are glad of me to spin them a yarn also.”[12] William asked Jemima to send two knitted worsted veils “of the blakest wool” for his nurses, both widows, “for they are very kind to me.”[13]

Though cheerful in his letters, he worried about her well-being: “…I sometimes drem me at home and in some kind of truble and then I think that you are meby unwell or something the matter with some of you…” He wondered if she had enough meal, whether little Charles was kept indoors “now that the cold weather sets in,”[14] and was grateful that her family helped pay their annual rent. Had the cow calved yet, and were the sheep free from scab?[15] William had paid into a seaman’s insurance fund and encouraged her to write to London via the local agent to access support.[16] Letters were a lifeline between the two:“…when I get a letter from you saying that you are well it just sets new life into me so I hope my dear that you will write when ever you can…”[17]

Jemima asked if the doctors had ever seen a knee like his and William replied: “There are three in this ward with the very same deseas just now and it is very comon.”[18] Unfortunately, there was no improvement. After six weeks, the surgeon determined that the amputation was necessary to relieve William’s suffering. The operation took place on October 5, 1876.

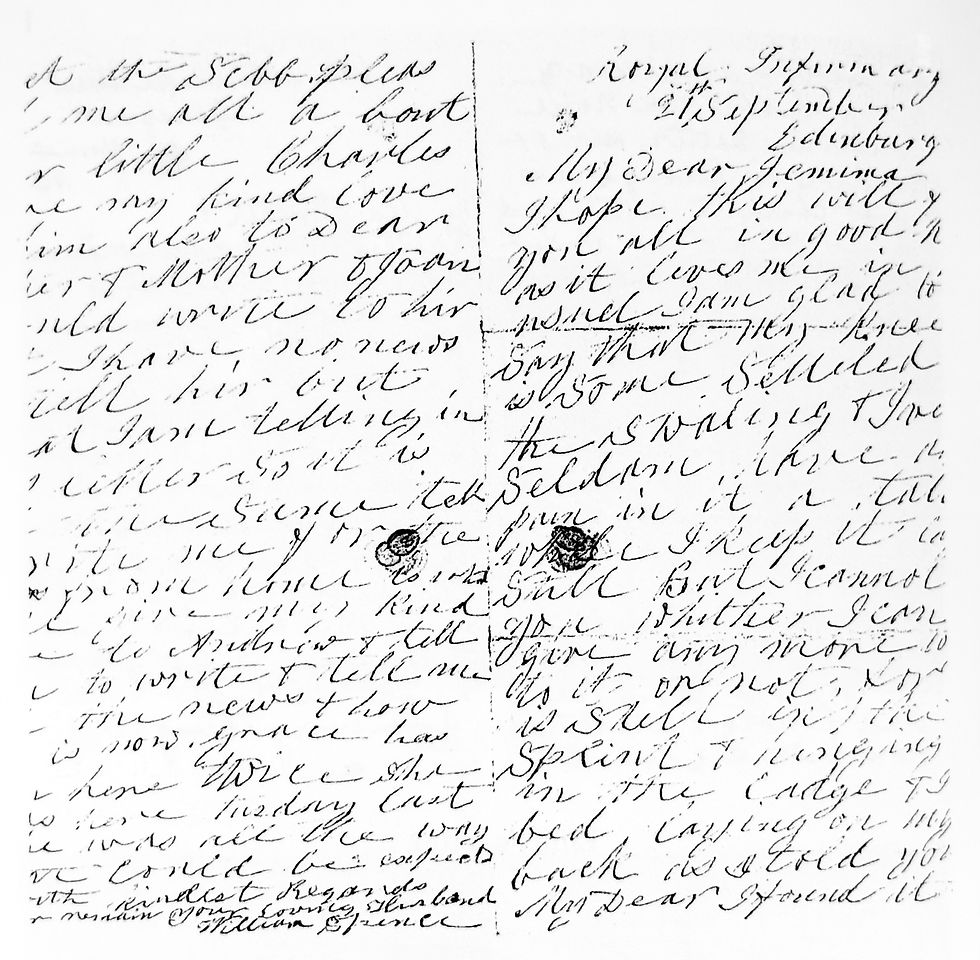

Nine days later, still bedridden, William had a hospital volunteer write home:

Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh

Oct 16th 1876

Dear Mrs Spence

Your dear husband wishes me to drop you a few lines to let you know that he is much better since he got his leg taken off if he keeps as well as he is and I hop so and he whises me to tell you not to give yourself any truble about him lousing his leg he is so thankfull to the Lord that he is relived of such a disces the proffesor said it was braking his constution fast and that taking it off was the only thing he could do to save his life… he could have written you himself but of course he is not sitting up in bed yet… and if it be the will of the Lord to spear his life and health you will all be provided for and all things work together for good to them that love God and he seems cherfull [19]

‘From which we may learn’

I was spellbound by the story woven through the letters and wanted to know more. What caused William’s diseased knee? Could I find hospital records to provide further insight? Researching the Royal Infirmary led me to an exciting discovery.

The Royal Infirmary aimed both to provide the best possible care to all patients and to improve medical knowledge through careful research and observation. In an 1879 speech, surgeon Joseph Bell (the inspiration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Dr. Watson) declared:

“We, to whom the public have entrusted the sick and wounded poor, underlie a double responsibility — to our patients, that we may treat them kindly, skilfully, and successfully; and also to the profession, that the experience which we gain in the priceless opportunities of the wards may not be lost. We cannot always be initiating new modes of operation or of surgical dressings, but to all of us are ever occurring cases from which we may learn.”[20]

I wondered if William’s amputation might be documented in the Edinburgh Medical Journal, which published detailed accounts of hospital cases. Page after page, I searched until finally, there he was. The doctor had provided a partial name for privacy, but it was undoubtedly him: William S., 36, fisherman, admitted 21st August 1876, disease of knee.[21]

Not only did Professor Spence detail the surgery, but he included a history of William’s affliction. Swelling in the knee had begun when he was seventeen, gradually worsening over nineteen years. Earlier that year, a blow to the knee—likely aboard the whaling ship—caused “both swelling and pain… [to be] so much aggravated” that the pain radiated to the hip-joint and became almost unbearable.[22] Given the timing, William may have fished that summer and then travelled to Edinburgh as soon as the haaf season ended—an excruciating endeavour.

To reduce the swelling, Professor Spence prescribed both iodide of potassium internally—what William described to Jemima as “plenty of inside medsns” and hot water fomentations to the joint (“a pice of cotton wading dipped in lookwarm water and wrong hard and then put over my knee with a thin gotaperge [gutta-percha] cover over it to keep in the steam”).[23]

Professor Spence operated, cutting through “the condyloid portion of femur,” just above the knee. A dissection revealed that the kneecap and the joint surfaces of the tibia and femur were severely diseased. Furthermore, there was a large cavity in the outside portion of the knee that contained “necrosed” bone.[24] Such joint destruction matches up with a couple of possible diseases common in the nineteenth century: tuberculosis of the knee or osteomyelitis (a bacterial infection of the bone). Before antibiotics, amputation was the only way to stop the infection and relieve suffering.

A perilous recovery

The surgery went well, but contrary to the reassuring letter he had the volunteer send home nine days later, William’s recovery was perilous. His “stump [was] dressed with lint steeped in boracic lotion” to help with healing, but on the evening of the third day his leg started to hemorrhage, his fever rose to 104 degrees Fahrenheit, and his pulse up to 132 beats per minute. Then, abscesses developed in his thigh. These were cut open and drained, and the wounds dressed with a disinfecting chlorinated soda solution.[25]

Slowly, William improved. One month after his surgery, on November 2, he wrote: “…my dear the wonnd is growing fast and looking well and I have no much pain in it but the confinement dos not a gree very well with me however I have got 4 weeks over which I trust is the worst.”[26] By December 8, he shared a milestone: “…on Monday night I got out and get on my close for the first time in 9 weeks and I have been at the fire every day since and might the Lord grant that I might contonue to be able to come out and so that I might get strong a gain.”[27]

By December 21, his progress continued:“I have been out of bed every day since I was out the first time and I can jump a bout the ward on the one foot and get myself a drink or anything that I want without the crutches alltogither and with the help of the crutches I can walk as fast as you could do unless you ware to run[.] My dear I find myself relieved of a very great triel by what I was feeling when I left you.”[28]

William spent the Christmas season in the hospital, making paper roses to decorate the ward. He received presents from the professor and his friends, “I got a fancy flannan shirt a pair of mits a mirchim pipe a Tabcco sack full of tabcco and a whole lot of Christmas cards and some toies for my Dear little Charles.”[29]

After several months of recovery and convalescence in Edinburgh, William was eager to get home and care for his family, though the long journey in the winter’s dark would be difficult on crutches and needed to be carefully planned:

Wilkie Place, North Leith

8th February 1877

… My dear I am thinking to be here a fortnight yet in purpose to have moon light to come home with for if I had to travel on the night I could not manadge without the light of the moon I might be still longer as a fortnight here for ought that I know however I will let you know if all well nixt letter I have been up at the Infirmary and seen the professer since I wrote to you last and got my misurs taken for a leg But the professer said that it would be a long time yet before he would a low me to try to walk on it for fear of hurting my limb… You most pleas write to me as soon as you receive this letter and let me know how long you think we have meal of our own crope to help us…

I ever Remain Dear Jemima your loving and Affect Husband

William Spence [30]

Faith in the face of uncertainty

William journeyed home successfully, was eventually fitted with a wooden leg, and returned to the haaf fishing to support his family. By the summer of 1881, he and Jemima had three children, with another on the way. During his hospital recovery, he expressed the belief that: “…the same God that has prosarved me in my gretest weakness will contenne his mercy to me to the last.”[31] I think of his words now, knowing what would happen five years later, on the night of July 20, 1881. William was the skipper of a sixareen, one of the boats that never made it back to Gloup Voe. Their boat foundered and his body washed ashore at the south beach of Westing.

A contemporary witness described the scene at Papil, Yell, when his coffin was landed: “His aged father and mother both came a distance of five miles to meet the body, and follow it to the grave. It was sad to see them, both old and white-headed, kneeling one at each side of the coffin (the lid had not been screwed down) taking a last farewell of their darling son and only support.”[32]

William’s faith in God’s mercy seems well-placed—though in an unexpected way. His body was one of the very few lost that night to be recovered and laid to rest. And it was his wooden leg, folk believed, that helped carry him to shore.[33]

Research request

As I continue piecing together the stories of the Gloup Disaster of 1881, I am always eager to learn more. If your ancestors were among the fishermen, widows, or children affected by the tragedy, I would love to hear from you. Any letters, photographs, or family stories are invaluable in helping bring these lives and experiences to light. You can reach me at: https://www.kareninkstervance.com/contact

Sources:

[1] Williamson, Jemima’s Journey, 70; Jemima Mann letter, December 1873.

[2] Catherine W. Williamson, Jemima’s Journey: Stories from the Herra, Yell, Shetland (Scotland: Myrebird, 2022).

[3] Ibid., 55; Charles Mann letter to sister, Jemima, 1 February 1874.

[4] Shetland Times, Saturday, 11 July 1885, page 3, “Letters to the Editor: The Edinburgh Royal Infirmary.” Shetland patients (who stayed in the infirmary and not with family or friends): 1879-80 (32), 1880-81 (24), 1881-82 (26), 1882-83 (32), 1883-84 (49).

[5] Shetland Times, Monday, 7 April 1873, page 2, “Wanted.”

[6] Williamson, Jemima’s Journey, 73; William letter, August 1876.

[7] Ibid., 74; William Spence letter, 28 August 1876.

[8] A. Logan Turner, Story of a Great Hospital: The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh 1729–1929 (Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1937), 194.

[9] Turner, Story of a Great Hospital, 195.

[10] D’Arcy Power, “James Spence,” in Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900, ed. Sidney Lee, vol. 53 (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1898), 336.

[11] Williamson, Jemima’s Journey, 74; William Spence letter, 28 August 1876.

[12] Ibid., 76; William Spence letter, 7 September 1876.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., 80; William Spence letter, 2 November 1876.

[15] Ibid., 77; William Spence letter, 21 September 1876.

[16] Ibid., 74; William Spence letter, 28 August 1876.

[17] Ibid., 76; William Spence letter, 2 November 1876.

[18] Ibid., 78; William Spence letter, 28 September 1876.

[19] Ibid., 78; Hospital volunteer letter, 16 October 1876.

[20] Joseph Bell, “Article III — Surgical Cases. Injuries and Operations,” Edinburgh Medical Journal 24, no. 9 (March 1879): 789–90.

[21] Professor James Spence, “Statistical Report of Results of Operations Performed by Professor Spence,” Edinburgh Medical Journal 25, no. 5 (November 1879): 389, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5317801/?page=5

[22] Ibid., 389.

[23] Ibid., 389.

[24] Ibid., 389.

[25] Ibid., 389-90.

[26] Williamson, Jemima’s Journey, 79-80; William Spence letter, 2 November 1876.

[27] Ibid., 80; William Spence letter, 8 December 1876.

[28] Ibid., 82; William Spence letter, 21 December 1876.

[29] Ibid., 83; William Spence letter, 29 December 1876.

[30] Ibid., 85-86; William Spence letter, 8 February 1877.

[31] Ibid., 80; William Spence letter, 2 November 1876.

[32] Shetland Times, Saturday, 30 July 1881, page 3, “The Recent Disaster.”

[33] Ibid.

Comments